Media Library | Writings | Dr. Alireza Nurbakhsh

The Meaning of Surrender

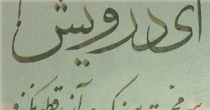

by Dr. Alireza Nurbakhsh

The first step on the path of Sufism is to surrender oneself to God. True surrender is not a self-conscious decision carried out as a result of a series of deliberations. It usually happens after years of frustration in finding the 'right' way to manage our lives, the right way to deal with others or to control our self-destructive behavior. Eventually, some seekers finally give up and surrender. They are driven to surrender, having no other choice; they understand wholeheartedly that this is the right thing to do.

But what does it mean to surrender oneself to God? Although I believe that the act of surrender is not fundamentally based on reasoning, that we do not surrender ourselves to God because there are convincing arguments for it, we can still enquire about the meaning of such an act. We can still ask questions such as what it means to surrender to God and how such surrender can be achieved.

From a linguistic perspective, surrender only makes sense in the context of fighting or resisting. If we have not been fighting with someone or something, it does not make much sense to surrender. In an ordinary fight, when we come to realize that fighting is pointless, we surrender. The same point applies in the spiritual realm. But who are we fighting against before we come to the realization that we must surrender ourselves to God? A tentative answer is other people. Other people usually get in the way of the fulfillment of our desires and wants. We spend countless hours, either in our minds or sometimes through words, or even physically, fighting with others. Some people are fortunate enough to realize that this is only the tip of the iceberg - that our animosity towards others is merely symptomatic of our own negative qualities. They come to realize that the real enemy is within and that to live in harmony with others we must first conquer ourselves. This enemy, in other words, is what the sufis have called the nafs or the ego. The obstacle standing between us and living in harmony with the rest of humanity is nothing other than our own self.

One example to illustrate this point is the quality of greed. Greedy people are never satisfied with what they have, always wanting something more. This quality will inevitably bring them into conflict with others. Greedy people who are fortunate will eventually realize that the source of the problem is not other people at all but rather themselves. They realize that their own greed is the source of all their conflicts with others; thus, they will try to control their greed instead of blaming others. Once we realize that the real enemy is our own ego, we may conclude that the solution lies in controlling the ego or even trying to obliterate it. We may begin in earnest to fight against our ego's desires and wishes. But if we are honest with ourselves, we will soon realize that our fight against the ego is a losing battle, and that we must give up the idea of winning this battle on our own. Let's return to the example of greedy people. We can imagine that once greedy people become aware of their greediness, they may devise various plans to stop themselves from acting in accordance with their greed. As an example, every time they feel greedy, they may go for a walk or try to meditate or do something to bypass their greed temporarily. But even so, they will still realize that the feeling of greediness is not going to leave them. They can only overcome their greed when they no longer feel the greed in themselves. This, however, is not something we can do out of sheer willpower. Though we may be able to stop acting greedily by sheer willpower, we cannot stop the feeling of greed. The realization that we are unable to do much to change our basic nature and that we must accept the way we are is the beginning of the path of surrender.

Once we come to the realization that fighting against our own ego does not get us very far, we realize that the way forward is to surrender to our condition. But what do we surrender and to whom do we surrender it? Surrender happens at the moment that we stop fighting against others and ourselves. We accept the way others are and also the way we are. We are not disturbed by other people's negative qualities or our own shortcomings. Once we accept the world as it is, as a manifestation of an all-encompassing Truth, we have surrendered ourselves to God. In surrendering ourselves to God, we realize that we cannot overcome our shortcomings on our own but rather must seek aspiration and help from without - be it from God or from our spiritual guide.

The essence of surrender to God is our acceptance of the world as it is. There is a story in the Bhagavad Gita illustrating this point about acceptance in a profound way. There was a sage who repeatedly pulled a drowning scorpion out of the Ganges and who was repeatedly stung for his efforts. Asked why he kept rescuing the venomous creature, the sage replied that it was the nature (dharma) of a scorpion to sting but that the nature (dharma) of a human being is to save.

In our contemporary culture, the act of surrendering is regarded as a passive and negative quality. Rather, we are encouraged to change ourselves and our environment, not to give up in the face of difficulties and never to surrender to our condition.

There is a sense that our culture is at odds with the idea of spiritual surrender as explained above. To the extent that the constant change in ourselves and the environment demanded by the culture creates conflict in us and the people around us, then such cultural norms are indeed incompatible with accepting the world the way it is. For instance, it is one thing to accept our greediness, but another to be encouraged to be greedy at the cost of destroying our environment; it is one thing to seek a job with a sufficient salary, but another to constantly change our jobs in search of more money and social status; it is one thing to excel in what we do, but another to do this at the expense of other people.

Yet in a fundamental sense, spiritual surrender does not have to be in conflict with the effort to better ourselves and our surroundings. Accepting the world the way it is does not mean that we should not or cannot contribute to its harmony and beauty. One of the hallmarks of those who have surrendered to God is that such people are no longer motivated and driven by self-interest since it is this quality that brings them into conflict with others, thereby terminating the path of their surrender. It goes without saying that it is only when we are not at war with ourselves and others that we become creative and sympathetic to others. After all, it is our essence to save.

Article taken from Sufi Journal, Issue 78, 2009

Other Writings by Dr. Alireza Nurbakhsh

-

Friendship

The Sufis refer to God as the Friend (dūst). This is based on the Koranic verse yuhibbuhum wa yuhibbuhunah (God loves them and they love Him, 5:45), which is interpreted by the Sufis as meaning that it is God’s love for us that gives rise to our love for Him.

Read more -

In Memory of My Dear Father

I would like to welcome everyone to this gathering to commemorate the death of my dear father, Dr. Javad Nurbakhsh, who passed away last Friday on the lOth of October 2008.

Read more -

Divine Love

The first time I read Rumi's story of Moses and the Shepherd, I was struck by the fact that the shepherd was much closer to God than Moses even though the shepherd's conception of God was not even remotely plausible. Years later, when I revisited this story, it appeared to me that Rumi had unravelled a deep mystery of divine love: in order to love God, one does not need to have a correct conception or description of God; what is required is a burning heart.

Read more -

The Master Disciple Relationship Revisited

The relationship between a master and a disciple has often been characterized in Sufism as that of unwavering trust, where the disciple follows the master without asking questions or raising objections in his or her journey towards the truth.

Read more -

The Experience of Nothingness

When I was about 13 years old, I was allowed to sit outside the main gathering place of the Sufis where my father conducted weekly meetings and the occasional vocal zekr. I don't quite remember the first time I sat outside the room listening to the vocal zekr, but I do distinctly remember the fir st time I heard my father utter these words: "Ilahi 'ajz wa inkesar, wa nisti 'ata befarma" (0 Lord grant us [the state of] helplessness, abjectness and nothingness).

Read more