Media Library | Writings | Dr. Alireza Nurbakhsh

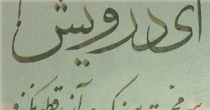

Friendship

by Dr. Alireza Nurbakhsh

The Sufis refer to God as the Friend (dūst). This is based on the Koranic verse yuhibbuhum wa yuhibbuhunah (God loves them and they love Him, 5:45), which is interpreted by the Sufis as meaning that it is God’s love for us that gives rise to our love for Him. Fakhruddin Iraqi, the 13th-century Persian Sufi, defines friendship with God as a relationship where God’s love precedes the spiritual traveller’s love for God. Put another way, God is the Friend because He instilled in us the experience of love and loving-kindness. One can interpret this to mean that from a Sufi point of view a friend is someone who leads us to experience love and friendliness.

But there is a deeper reason for referring to God as the Friend. This is, I believe, to highlight that through the act of friendship one can experience oneness. By this I mean the experience whereby we do not “see” ourselves as being separate from others. This gradual loss of focus on the self may begin with feeling empathy with others, then grow into a sense of identification with others and sometimes culminate in the experience of oneness, in which one is no longer conscious of any separation between oneself and other people. Muhammad Shirin Maghribi, the 14th-century Persian Sufi, has written the following poem about such an experience:

That spiritual friend knocked at my door last night.

“Who is it?” I asked. He answered, “Open the door. It is you!”

“How can I be You?” I asked. He answered, “We are one,

but the veil has hidden us in duality.”

We and I, he and you, have become the veil,

And how well this has veiled you from yourself!

If you wish to know how we and he and all are one,

Pass beyond this ‘I’, this ‘we’, this ‘you’.

The act of friendship is different from the act of loving. In a relationship of friendship both parties care for each other and give and receive benefits from each other. This reciprocity may not exist in the act of loving, for we may love someone without our beloved giving anything in return or even knowing that he or she is being loved by us.

Aristotle was one of the first philosophers in antiquity to write about the nature of friendship. In his Nicomachean Ethics he sets forth three main reasons why people become friends with one another. These reasons are pleasure, utility and good character. Of these, Aristotle believed that only a friendship based on good character can turn out to be a perfect friendship. This is because it is only in such a friendship that one likes or loves the other person for the other person’s sake. In friendship based on pleasure or utility, though we may confer benefit to our friend, our basic motive is to receive benefit for ourselves.

According to Aristotle, a true friend is one who not only likes us for who we are but also one who wants what is good for us. Friendship is a relationship of reciprocal goodwill in which each party likes the other party for the other person’s sake, always wanting what is good for the other.

There are two aspects of Aristotle’s view of friendship that are relevant to our understanding of friendship from the Sufi point of view. The first aspect is that a perfect or true friendship should not be based on any ulterior motive. The more we like someone for who they are, the closer we get to not experiencing our “self” in the act of friendship. The stripping away of ulterior motives in our friendship with others brings us closer to the experience of oneness, for it is our desire to benefit ourselves first and foremost that keeps us from this experience.

The second aspect of Aristotle’s theory of friendship is what he called eunoia, meaning “goodwill” or “wanting what is good for the other.” Aristotle does not explain it, as he may have thought that this concept is sufficiently clear. From the Sufi view of friendship, “wanting what is good for the other” not only means to confer benefit on the other but also encompasses two other fundamental principles.

The first principle is the acceptance of one’s friends as they are, without criticizing them for their shortcomings. Friends do not “see” any faults in each other because each “sees” the other as being part of the whole, the One. There is a story about Ibrahim Adham, a 9th-century Persian Sufi from Khorasan, who was once visited by a stranger. The guest stayed with Ibrahim for a few days and when he was about to leave, he asked Ibrahim to make him aware of any faults that Ibrahim had noticed during his stay. Ibrahim replied, “I looked at you with the ‘eye’ of friendship and therefore everything about you was pleasant to me.”

The second principle is that for Sufis goodwill should be understood as wanting what is good for other first and foremost and prior to wanting what is good for oneself. One’s friends always have priority over oneself.

Sufis also refer to their spiritual guide as a friend, and the relationship between master and disciple in Sufism is often depicted as one of friendship. The meaning of “goodwill” in this context, however, becomes different. It seems that for Aristotle both the giver and the receiver of goodwill should be cognizant of the act of goodwill. This is how friends enjoy and appreciate their friendship, and this is also implied in my discussion above about friendship and Sufism.

But in the context of the spiritual guide’s relationship with the disciple, “what is good for the other” may not be what disciple wants; instead it may be unpleasant or even painful. This is because most of us are prisoners of our own ego and therefore consider the behavior of others toward us as “goodwill” only if it satisfies our own desires and wishes. A spiritual guide in Sufism is someone who, without any expectation of appreciation or gratitude, creates every opportunity for us to confront our nafs (ego) and realize our own imperfections and then helps us overcome our shortcomings. This can sometimes evoke in us pain or anger at our guide, as we usually react negatively when people show us our own shortcomings.

Rumi in his Mathnawi, tells the story of Dhu’l-Nun, a Sufi master who lived during the 9th-century and was put away in an asylum by his own people because they could not tolerate his strange behavior. One day a group of Dhu’l-Nun’s so-called friends decided to visit him. As they were about to enter his room, Dhu’l-Nun asked them who they were; they replied that they were his friends. As soon as Dhu’l-Nun heard this, he began acting like a madman and cursed them, whereupon they all fled.

Dhu’l-Nun burst out laughing, shaking his head,

“Look at the hot air of my so-called friends.”

A true friend never feels burdened by the suffering of another,

The kindness of a friend is like a shell engulfing one’s suffering.

The sign of friendship cannot be found in good times,

It is at times of calamity and suffering that we come to know our friends.

A friend is like gold and one’s suffering resembles fire.

Pure gold remains blissful in the midst of fire.

Dhu’l-Nun’s behavior was indeed an act of goodwill although his so-called friends did not have the insight to perceive it as such. He gave them an opportunity to realize their own hypocrisy and insincerity—an opportunity that they did not perceive or embrace—and thus he continued to pay the price for his goodwill, remaining confined in the asylum.

What Dhu’l-Nun’s friends lacked was the quality of trust in their friend. It is through trust of our friends that we give them the opportunity to expose us to their essential kindness. It is through trust that we can accept our friends the way they are and believe that ultimately they want what is good for us. The expression of “trust in God” means to accept, in a profound sense, what happens to us in the course of our lives because God as friend always wants what is good for us although we may not always perceive it as such.

Article taken from Sufi Journal, Issue 82, 2012

Other Writings by Dr. Alireza Nurbakhsh

-

In Memory of My Dear Father

I would like to welcome everyone to this gathering to commemorate the death of my dear father, Dr. Javad Nurbakhsh, who passed away last Friday on the lOth of October 2008.

Read more -

Divine Love

The first time I read Rumi's story of Moses and the Shepherd, I was struck by the fact that the shepherd was much closer to God than Moses even though the shepherd's conception of God was not even remotely plausible. Years later, when I revisited this story, it appeared to me that Rumi had unravelled a deep mystery of divine love: in order to love God, one does not need to have a correct conception or description of God; what is required is a burning heart.

Read more -

The Meaning of Surrender

The first step on the path of Sufism is to surrender oneself to God. True surrender is not a self-conscious decision carried out as a result of a series of deliberations. It usually happens after years of frustration in finding the 'right' way to manage our lives, the right way to deal with others or to control our self-destructive behavior.

Read more -

The Master Disciple Relationship Revisited

The relationship between a master and a disciple has often been characterized in Sufism as that of unwavering trust, where the disciple follows the master without asking questions or raising objections in his or her journey towards the truth.

Read more -

The Experience of Nothingness

When I was about 13 years old, I was allowed to sit outside the main gathering place of the Sufis where my father conducted weekly meetings and the occasional vocal zekr. I don't quite remember the first time I sat outside the room listening to the vocal zekr, but I do distinctly remember the fir st time I heard my father utter these words: "Ilahi 'ajz wa inkesar, wa nisti 'ata befarma" (0 Lord grant us [the state of] helplessness, abjectness and nothingness).

Read more